In the five or six

years I have spent investigating the 34 common cinematic plot patterns, I have broken down and analyzed the structures of literally

hundreds of popular films. I have since used the best, most

prototypical examples I could find to illustrate each particular

pattern on this blog and my book Screenwriting & The Unified

Theory of Narrative, Part II.

However, this pool of study films has always had one shortcoming: it

was limited to movies I personally own or have access for close

study. While my personal movie collection is quite large, it is far

from an exhaustive library of every excellent film made over the last

fifty years. As such, there have been many popular films

conspicuously absent from my writings. In my free time over the past

month, I have sought to remedy this issue. As you shall see from the

list below, I have identified for the first time the plot patterns

contained in over two dozen popular favorites.

Also

included on this list are films I viewed very early in my

investigation, back when I had only a vague conception of the shape

of the various patterns and before I began mapping out each film plot

point by plot point. As such, there were films whose pattern I could

not yet identify or initially miscategorized. As I now realize (and

as you shall read below) the patterns of these films were difficult

to identify because many take advantage of the alternative options

found in each pattern or contained acceptable deviations from the

prototypical norm. As a result, analyzing these deviant examples

reveals the flexibility of cinematic plot patterns. Plot patterns are

not rigid formulae, but have the capacity to bend and stretch to

accommodate individual story premises and artist intentions while

still producing effective, well-received narratives.

The

bottom line is that the following overlooked films continue to

confirm my theory of the 34 Common Plot Patterns of American Cinema.

Some have just proven more difficult to analyze due to their use of

alternatives, deviations, combo patterns, hybrid patterns, or their

use of dual or triple protagonists.

(Warning: Lots of

SPOILERS ahead.)

The Cider House Rules (1999)

Let’s

start with a simple one. The Cider House Rules

is a Type 5a: The Escapist, one of the most commonly-seen Hollywood

plot patterns. The pattern offers a wealth of prototypical examples

in all shapes and sizes, from Lawrence of Arabia

to Office Space, Coming to America to

American Beauty, Dances With Wolves

to The Nightmare Before Christmas, Tootsie to

Trainspotting. To

summarize, the Escapist begins with a protagonist who has grown

dissatisfied with his or her life or environment, roles or

responsibilities. At the end of Act 1, the protagonist abandons this

current reality to escape into what he or she sees as a more pleasing

alternative. Things first go well in this new way of life. However,

it proves to be a fool’s paradise. Unwelcome doses of reality begin

to invade the protagonist’s happy refuge in late Act 2A, bringing

the carefree paradise to a potential end at the Midpoint. Yet rather

than return to reality or face its problems, the protagonist

formulates a second alternative: an Option C. Act 2B follows the

pursuit and ultimate demise of Option C, resulting in an end-of-act

crisis event. Here the protagonist must make a difficult choice:

either return to the former reality to face its problems directly

(and/or take responsibility for past mistakes), or continue to deny

the reality of the situation by attempting to escape even further—a

foolish path which leads to a sad or ignoble end.

We

can see this pattern quite clearly in The Cider House

Rules. The protagonist Homer

Wells (Tobey Maguire) has lived his entire life at St. Cloud

orphanage. During that time, Homer has become the skilled assistant

of Dr. Wilber Larch (Michael Caine), the man who not only runs the

orphanage, but performs abortions and births the babies of unwed

mothers. Homer is expected to become Larch’s successor. But Homer

is young and restless, never having stepped foot off the orphanage

grounds. In addition, he secretly questions the moral necessity of

Larch’s work. At the end of Act 1, Homer seizes an opportunity to

escape. In Act 2A, Homer enjoys the rustic life of an orchard worker

and begins to fall in love with Candy (Charlize Theron). Meanwhile,

trouble is brewing at St. Cloud’s. Dr. Larch may lose control of

the orphanage unless Homer returns as Larch’s official successor.

However,

when apple-picking season ends at the film’s Midpoint, Homer

ignores Larch’s letters urging his return, opting to stay on his

own to begin a love affair with Candy while her boyfriend Wally (Paul

Rudd) is away at war (Homer’s Option C). While this again goes well

for the first half of Act 2B, the new path begins to fall apart when

Wally is wounded in battle and set to return. Homer’s destiny also

rears its head when he must perform an abortion on fellow worker Rose

(Eryka Badu) after she is impregnated by her own father. A double

tragedy then permanently ends Homer’s escape at the end of Act 2B:

Rose kills her father and runs away; Dr. Larch dies of an accidental

overdose. With this, Homer chooses to return to the reality from

which he originally sought escape, and saves St. Cloud orphanage by

accepting his destiny as its new caretaker.

Home Alone (1990)

Home Alone

is also an Escapist narrative, but demonstrates an interesting

alternative to the pattern’s central premise. Rather than a

protagonist escaping his/her unhappy reality, everything undesirable

about that reality escapes the protagonist. Eight year-old Kevin

(Macaulay Culkin) hates being the youngest child in a house packed

full of obnoxious family members. He hates it so much that he wishes

out loud that his whole family would disappear. By a twist of fate,

Kevin is accidentally left behind when his family leaves for

vacation, fooling Kevin into believing he has gotten his wish. Kevin

has escaped his family.

Just

like the Act 2A of any Escapist narrative, Kevin first finds his new

family-free world to be a child’s paradise. But Kevin soon realizes

that life alone can be difficult and frightening, especially when

burglars Harry and Marv (Joe Peschi & Daniel Stern) start

snooping around the house. At the Midpoint we find another necessary

deviation from the standard pattern. While most Escapist protagonists

(like Homer Wells) consciously avoid a return to their former reality

in favor of an Option C, the story circumstances of Home

Alone preclude the possibility

of return at the moment. Furthermore, Kevin does not even realize

return is an option, as he believes he has permanently wished his

family away. Therefore, in response to the Midpoint event, Kevin must

transition from simply enjoying his private paradise to a quest to

hide his secret solitude in order to protect himself and his home.

However, this Option C falls apart when Harry and Marv discover

Kevin’s secret at the end of Act 2B.

Kevin

now prays aloud for his family’s return. He has had enough of his

escape and wants to return to his previous reality. While Home

Alone’s Act 3 is comprised

mostly of the comic hijinx of Harry and Marv’s botched home

invasion, it ends with Kevin welcoming his family back with open

arms. Kevin has learned that, while escape was fun, a stable family

life with people who care and watch over him is far more preferable.

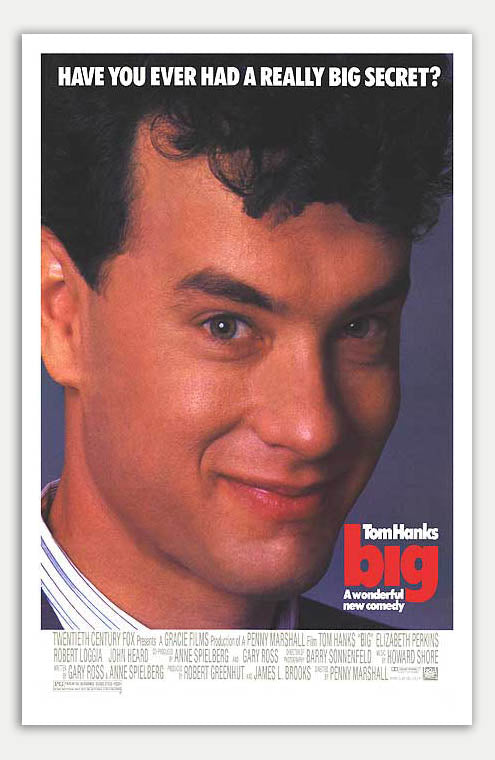

Big (1988)

Let’s

move on to the next plot pattern, Type 5b: The Ejected. I am happy to

find three new

examples of the Ejected since, as one of the more rarely-seen plot

patterns, I have previously had only a shallow pool of cases for

study. As for prototypes, the best I could find for Unified

Theory of Narrative were Jerry

Maguire (1996), Darren

Aronofsky’s The Wrestler

(2008), and the Paul Newman poolhall classic The Hustler

(1961). The pattern’s name issues from its first act, where the

protagonist initially pursues a flawed, ill-advised, or naive

ambition. (Jerry Maguire’s manifesto to his sports agency calling

for systemic change; Randy “the Ram” chases his fading glory as a

professional wrestler; Fast Eddie challenges Minnesota Fats before he

is ready.) The protagonist’s errors in judgment have the

consequence of forcibly EJECTING the protagonist from his/her world

at the end of Act 1. (Jerry is fired from his agency; Randy has a

heart attack and can no longer perform; Fast Eddie loses in

spectacular fashion and is left broke and destitute.) Act 2A then

sees the protagonist exiled, wandering in the wilderness, seeking out

allies and new paths to hopefully get his/her life back together and

hopefully find a way to return to the original ambition.

This

pattern is found quite clearly in the first half of Big.

Thirteen year-old Josh Baskin feels the frustrations of being stuck

between childhood and adolescence, wishing he could simply skip over

this awkward stage of his life. In a fateful moment, Josh expresses

this ambition to a magical “Zoltar” machine and awakes the next

morning transformed into a 30 year-old man. The consequences of

Josh’s wish completely eject him from his 13 year-old world. He

cannot even remain at home, as his mother is terrified of this

stranger calling himself her son. Josh and his best friend Billy

decide that Josh’s only option is to enter the wilds of New York

City and try to survive as an adult until they can find a way to

reverse Josh’s wish. While first scared and confused, Josh manages

to get a job, find some allies, even score a major promotion. Yet

Josh remains an outcast; a 13 year-old trapped in a 30 year-old’s

world.

The

Ejected pattern is further distinguished by a “Great Compromise”

at the story’s Midpoint. Here, the protagonist chooses to

compromise his/her original ambitions, long-term objectives, ethics,

or integrity in favor of some immediate gain. In some cases, this is

a potentially positive path which is then sabotaged by the

protagonist’s personal flaws (as seen in The Wrestler).

More often, this is an ill-conceived path motivated by the

protagonist’s Flaw which leads the character further away from

his/her required personal change. (In Jerry Maguire,

the emotionally-needy Jerry begins a romantic relationship with, and

eventually marries, his assistant Dorothy even though he does not

love her. In The Hustler, Fast

Eddie makes a deal with seedy manager Burt to earn the money to play

Fats again.) In Big,

Josh makes this compromise by choosing to blow off his best friend

Billy to start an adult relationship with his coworker Susan. Over

the rest of Act 2B, Josh forgets his desire to return to his 13

year-old life (much to Billy’s disgust) in favor of the life of a

mature adult. Yet by the end of the act, Josh comes to realize this

is the wrong path. He recognizes all he will miss by remaining an

adult.

Thus,

in typical Ejected fashion, the protagonist’s moment of Crucial

Decision occurs at the start of Act 3 (not at the Midpoint, as in

most patterns). Josh runs out on his big business meeting, abandoning

everything he has achieved as an adult, to find the Zoltar machine

that will change him back into a kid. As in most Ejecteds with

Celebratory “up-endings,” the film ends with the protagonist

successfully returning to the original world.

The Shawshank Redemption (1994)

I

do own a copy of The Shawshank Redemption and

have used it for study many times. However, until now, the film

had perplexed me in terms of its

plot pattern. Shawshank has

never been an easy film to analyze from a structural standpoint. It

lacks the clear Problem > Goal > Path of Actions spine found in

most Hollywood films. Nor is there an overtly-defined

protagonist-antagonist conflict. Instead, Shawshank

contains a long, episodic yarn

covering over thirty years of story time in which the forces opposing

the protagonist often shift or fade. As such, it is difficult to put

a finger on various structural elements in the way one might for a

more traditional, action-oriented movie. For instance, I originally

mused that Shawshank might

be a highly abstract take on the Destructive Beast plot pattern (a

pattern which contains, among many others The Terminator)

where the “Beast” is the despair determined to consume

protagonist Andy Dufresne (Tim Robbins). But that was just silly.

No,

it is now clearly obvious that The Shawshank Redemption

follows the Ejected pattern. The reason it took me so long to realize

this comes from a significant deviation in Shawshank’s

opening act. The easiest way to recognize an Ejected is by the End of

Act 1 Turning Point whereby the protagonist is forcibly expelled from

his/her former environment. However, in Shawshank,

this event is used as the inciting incident (Andy is convicted of

murder and sentenced to life in Shawshank prison). In fact,

Shawshank compresses

the entire Act 1 of a regular Ejected into its first six and a half

minutes. The second sequence of Shawshank’s

Act 1 then picks up where an Ejected’s Act 2A usually begins; with

the protagonist lost in the new wilderness. For its own End of Act 1

Turning Point, Shawshank instead

uses the plot point where the protagonist takes the first step toward

establishing a place in his new world: the moment when he befriends

Red (Morgan Freeman). (This is comparable to the moment in Big

when Josh gets a job in New York.)

The

rest of Shawshank,

however, follows the Ejected pattern quite closely. This is made most

obvious by the clear Great Compromise found at the story’s

Midpoint. Warden Norton takes advantage of Andy’s intellectual

pride (Andy’s Fatal Flaw) by making him the prison’s unofficial

accountant, a role which tangles Andy in Norton’s crooked

schemes, essentially making Andy a criminal accomplice. This turns

out to be a foolish path which leads to Andy’s ruin at the end of

Act 2B. Andy, given a chance to prove his innocence, is crushed under

Warden Norton’s power out of the fear that Andy will reveal the

prison’s secrets upon his release.

Shawshank

again deviates somewhat from the norm in Act 3 by the simple fact

that the protagonist disappears into thin air at the first turning

point. Yet as the remaining act fills in the narrative gaps behind

Andy’s disappearance, we see that Andy’s Act 3 course of actions

follows the same path as Josh's in Big:

Through self-reflection and personal evaluation, Andy makes his

Crucial Decision at the start of Act 3. Finally purged of his flaws,

Andy chooses to take the actions necessary to return to world from

which he was originally ejected.

Rushmore (1998)

Well,

this is embarrassing. In the past, I have used Wes Anderson’s

Rushmore as a

prototypical example of Type 3a: Crisis of Character, both in this past article

and in my book Screenwriting

& The Unified Theory of Narrative.

However, one thing about Rushmore

never completely meshed with the Crisis of Character pattern – its

Act 2B. I have now come to realize that Rushmore

is

NOT a Crisis of Character, but yet another Ejected.

It

is an easy mistake to make. The Crisis of Character and the Ejected

are very similar in terms of their first two acts. As already

covered, the Ejected begins with a flawed protagonist who, through an

ill-conceived ambition, ends up ejected from his/her former world at

the end of Act 1. Act 2A then finds the banished protagonist seeking

a new path, hopefully to make an eventual return. In comparison, the

Crisis of Character begins with a deeply-flawed protagonist who lives

a self-satisfying life in a private, socially-isolated niche. (Think

of Shrek [2001]

or As Good as it

Gets

[1997].) Unexpected events cause Act 1 to end with the loss of this

precious niche. Act 2A then starts with the protagonist taking

actions intended to regain the niche. The line between “ejection”

and the “loss of a niche” is fairly thin. The main difference is

that the former suggests a more forcible expulsion which is in some

way the protagonist’s own fault. In the latter, the loss more often

comes through a twist of fate or stroke of bad luck. (In Shrek,

the titular character’s private swamp is suddenly turned into a

ghetto for banished fairy tale creatures. In As

Good as it Gets,

OCD-ridden Melvin Udall’s (Jack Nicholson) tightly-regulated life

is disrupted when Carol the waitress is no longer able to serve him

at his daily eating place.)

The

action in Rushmore

blurs the line between these two patterns. Narcissistic teen Max

Fisher (Jason Schwartzman) has created a private wonderland out of

his life at Rushmore Academy (Max’s niche). An infatuation with

teacher Miss Cross (Olivia Williams) motivates Max to launch a crazy

scheme to impress her—a plan which gets Max expelled from Rushmore

Academy at the end of Act 1. Rushmore’s

Act 2A blurs the lines to an even greater degree. The act is

comprised mostly of Max’s efforts to make the best of his new life

in public school (with the hope of being invited back to Rushmore)

with the help of Miss Cross and Mr. Blum (Bill Murray). But is this

an attempt to chart a new path in the wilderness, or a quest to

regain the lost niche?

Rushmore’s

Act

2B then cracks the case wide open. In a Crisis of Character, the

Midpoint presents a moment when the protagonist, through his or her

increasing interactions with other people, comes to realize

that there is something better in life than his or her isolated

niche. The protagonist comes to desire a closer connection with

another character. In Act 2B, the protagonist largely forgets about

the niche in favor of pursuing this healthy, more positive

relationship. This does not happen in Rushmore.

Here,

the Midpoint involves Max’s discovery of the secret love affair

that has developed between Mr. Blum and his crush Miss Cross. In

response, Max launches a savage campaign of revenge, believing this

will free Miss Cross for his own affections. This, of course, is a

very poorly thought-out Great Compromise of Max’s original

ambitions. And, like in Shawshank,

this path leads Max to the bottom of a deep, dark pit by the end of

Act 2B.

To

be honest, I should have identified Rushmore

as an Ejected right away by the placement of the Character Arc's Moment of Crucial

Decision. In a Crisis of Character, the

Crucial Decision typically occurs at the story’s Midpoint. In the

Ejected (as already mentioned) it happens at the beginning of Act 3.

Indeed, it is not until the start of Act 3 that Max finally realizes

what a selfish jerk he has been and takes the necessary actions to

make amends. A Celebratory Ejected need not always end with the

protagonist’s return to the original world. Alternatively, the

story can end with the protagonist finding a new life which is just

as satisfying, or even more so than the original. This is how Jerry

Maguire

ends, and this is also what occurs at the conclusion of Rushmore.

Up (2009)

While

we’re on the subject of the Crisis of Character, let’s talk about

Disney/Pixar’s Up. Up checks off most of the boxes of

a prototypical Crisis of Character.

Flawed,

antisocial protagonist? (Carl is a misanthropic curmudgeon.) Check.

A

socially-isolated niche which the protagonist loses at the end of Act

1? (After the death of his wife, Carl has shut himself off from the

world in his old house. By court order, Carl is evicted from his

house, which is then to be bulldozed.) Check.

A

quest to regain that isolated niche (or a niche of equal or greater

value) in Act 2A? (Carl lifts his house off the property on a quest

to live the rest of his life alone at the top of Paradise Falls.)

Check.

A

“Character of Disapproval” whose function is to continually

criticize the protagonist’s flaws in order to nudge the protagonist

toward personal change? (Young explorer scout Russell winds up stuck

tagging along on the adventure.) Check.

A

Moment of Crucial Decision where the protagonist decides the niche is

no longer so important, and gives it up in favor of a greater

personal connection with other characters? Check.

Yet,

there are also some clear discrepancies in Up. For starters,

there is an uncommon amount of action and adventure in Up’s

second half. There are also additional characters and story elements

which do not fit the Crisis of Character’s norms. When Carl and

Russell reach the island of Paradise Falls, they encounter a giant

prehistoric bird (who Russell names “Kevin”) chased by

superintelligent dogs. Carl learns the dogs belong to his childhood

idol Charles Muntz. Muntz is on an obsessive quest to capture Kevin

at all costs. While first in awe of Muntz, Carl soon realizes Muntz

has gone dangerously mad. Russell begs Carl to defend Kevin from

capture. Yet Carl is apathetic to the bird’s plight – until

Muntz’s mad actions put Russell in danger. With this, Carl puts all

personal concerns aside and rises to the occasion, heroically

opposing his former idol to save Russell and Kevin.

This

summary also sounds familiar. It is a simplified version of the

Crisis of Character’s sister pattern, the Crisis of Conscience. As

exemplified by films like Casablanca, On the Waterfront, and

Schindler’s List (and discussed in detail in this previous article), the Crisis

of Conscience begins with a protagonist allied on the side of a Force

of Darkness (Carl has been a lifelong devotee of Charles Muntz). A

Victim/Advocate character then begs the protagonist for help against

the Force and its evil deeds (Russell asks Carl to save Kevin from

capture). Though this creates a moral dilemma, the protagonist

resists these pleas until the Force commits an action so

unconscionable that the protagonist can no longer look the other way

(Russell’s life is put under threat by Muntz). The protagonist then

turns on the Force of Darkness and transforms into a selfless hero.

Up

is therefore a hybrid Taking on the Mantle, incorporating plot and

character elements from both of its subtypes. (Hybrid patterns are

briefly explained in this article.)

As an added note, Iron

Man

(2008) is also a hybrid Taking on the Mantle (as discussed in detail

in this article),

although Iron

Man combines

the elements of the Crisis of Conscience and the Crisis of Character

in a much different way. In any case, you can sound smart if anyone

ever asks you what Up

and

Iron Man

have in common.