Those who make regular visits to

this blog should already be familiar with my concept of the 16 Common Plot Types. In my studies of narrative, I have discovered

that nearly every well-made traditional Western-style film for the

past fifty years or more (which for brevity we may call “Hollywood

film,” though that label can be too limiting) contains a plot that

fits with shocking consistency into one of sixteen patterns. The most

surprising thing about this discovery is how extremely different

films can share the exact same pattern, plot point for plot point,

even though they seem to have nothing else in common on their

surfaces.

In this article and the next, I

will explore another of these plot types. This time, it is #6 on my

list, which I have labeled The Unstoppable Beast.

As defined

in previous articles, The Unstoppable Beast contains a story in

which:

A innocent hero is targeted by some malevolent force, a force that

will not stop until the hero is destroyed. Plot develops as each

escalated attempt by the protagonist to escape the force is denied.

Finally, in the end, the hero chooses to fight back.

As

I have found in other plot types, the Unstoppable Beast can be broken

down further into two distinct subtypes. In the first subtype, the

malevolent force has the single-minded goal of killing, ruining, or

in some other sense destroying the protagonist, and will stop at

nothing until this is accomplished. I will call this the The

Destructive Beast.

In the second, the malevolent force does not wish to physically

destroy the protagonist, but rather to possess

the protagonist. The force's goal is to destroy the protagonist's

personal will so it may own, control, or even love the protagonist

against the protagonist's will. This will be called The

Covetous Beast. Though

these subtypes share the same general premise, they differ

significantly in their essential characters and major plot events.

For this reason, Part One of this article will focus on the

Destructive Beast while the Covetous Beast will be explored next

month.

THE DESTRUCTIVE BEAST

To

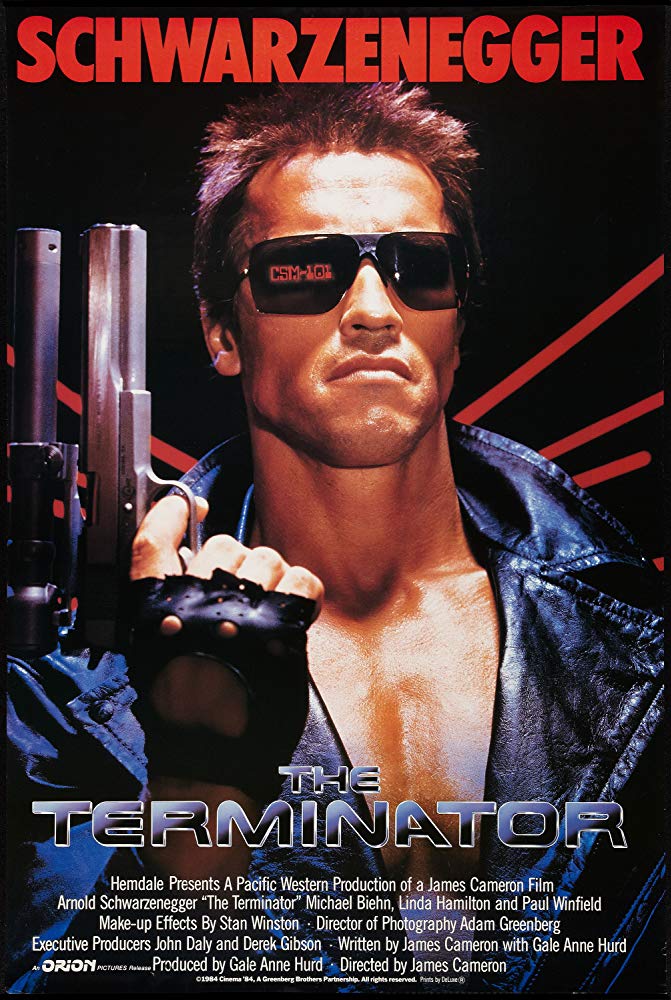

demonstrate both subtypes, I will make use of three study films. The

first will contain a simple storyline which is easy to recognize as a

member of this group. Here, the obvious choice is James Cameron's The

Terminator (1984).

The

second film must contain a more sophisticated story, yet one with

clear similarities to the first. Here we will use The

Bourne Identity

(2002).

Finally,

our third film will be an oddball, one that on its surface seems to

have nothing in common with the other two. Here I have chosen Paul

Thomas Anderson's 2002 misfit romance Punch-Drunk

Love.

(These are, of course, not the

only examples. I have found this subtype in thrillers (The

Marathon Man), comedies (Pineapple Express), comic-book

fantasy (The Incredible Hulk), even family films (Lemony

Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events)

All three of these films share

identical threads in terms of their main story conflict. A relatively

innocent protagonist is targeted by a vicious, single-minded

antagonist (“The Beast”) who pursues the protagonist with

escalating actions until one of them are destroyed. In The

Terminator, Sarah Connor is

pursued by a killer cyborg programmed to kill her at any cost.

Similarly, in The Bourne Identity,

Ted Conklin uses the CIA's god-like powers to find and kill Jason

Bourne. In Punch-Drunk Love,

the sweet and simple Barry Egan (Adam Sandler) is terrorized by a

sleazebag extortionist (Philip Seymour Hoffman) who seems hellbent on

ruining Barry's life.

What

first must be noted is what it means to call these protagonists

“innocent.” Put simply, this means, from an audience standpoint,

these characters do not deserve the persecution they receive from the

Beast. Sarah Connor wouldn't harm a fly and wants nothing more than

to live her simple life. Barry Egan is as meek as a sheep and simply

wishes the world to leave him be. When we first meet Jason Bourne,

his memory has been wiped as clean as a newborn's and merely wants

to learn who he is and how he fits into the world. Yet this is not to

say that the Beast targets the protagonist without reason. In every

case, the protagonist does something (or in the case of Terminator,

will do something) that, while

seemingly harmless, brings him or her to the Beast's attention and

leads the Beast to decide the protagonist deserves destruction. Sarah

Connor will give birth to the man who will someday be the Beast's

greatest threat. Therefore, she must be terminated. Jason Bourne

investigates his identity, leading Conklin to believe Bourne has gone

rogue and must be eliminated. Barry Egan calls a phone sex line out

of loneliness, causing his Beast to label him a lowlife pervert

who deserves exploitation.

A

second essential trait of these stories is the single-minded focus of

the antagonist. Once the Beast locks onto the protagonist, its

efforts never waiver. It will pursue, and continue to pursue, with no

change except for escalation. They are heat-seeking missiles. No

matter how the protagonist zigs or zags to escape, the Beast will

keep after the protagonist until he or she is utterly destroyed.

Terminator's killer

cyborg is Hollywood's prime example of such an antagonist, but even

the low-level sleazeball who terrorizes Barry Egan demonstrates this

same vicious obsession. He could at any moment decide enough is enough

and stop harassing Barry, yet seems to take it as a point of personal

pride to go after Barry harder and harder every time Barry makes any

attempt to stand up for himself.

It

should also be noted that, like most concepts in screencraft, the

concept of the Beast is flexible in terms of its execution. It may be

interpreted literally or figuratively. The Beast may be a single

character acting alone, or it may be a larger collective of which the

antagonist acts on behalf. It's not the killer cyborg's idea to kill

Sarah Connor. It is acting on the orders of the artificial

intelligences that rule the future. Ted Conklin does not pursue

Bourne out of a personal vendetta, but acts as a representative of

the entire CIA. The Beast may directly attack the Protagonist, or it

may act through proxies. Conklin's assassins and the goons that

harass Barry Egan act as extensions of the Beast. Depending on how

abstract your thinking, the Beast can even be a cosmic force. I have

even mused in the past that The Shawshank Redemption acts

as an Unstoppable Beast, where the Beast is the feeling of hopelessness

and despair that seeks to devour Andy Dufrene (albeit, this is a pretty big stretch).

Besides

the Protagonist and the Beast, the Destructive Beast subtype

typically contains a third major player. In his or her flight from

the Beast, the Protagonist attaches him or herself to a person who

will serve as a Sole Companion character. This character, often

doubling as a Love Interest, becomes the only person the Protagonist

can truly count on. We have Reese in Terminator,

Marie in Bourne, and

Lena in Punch-Drunk Love.

The Sole Companion not only assists the Protagonist in his or her

struggle, but more importantly provides the support, love, and

reassurance the Protagonist desperately needs to continue against

insurmountable odds. Though not absolutely essential for this subtype to function (for example, The Marathon Man

forces the Protagonist to fight the Beast all on his own, and stories

with group protagonists seem to have no need for the character), this

relationship usually serves a crucial narrative role. It not only

adds complexity to what might be an overly-simple plotline, but also

becomes a key factor in both the Protagonist's character

transformation and the ultimate expression of the story's theme (this

is discussed in greater detail later in this article).

I

have also noticed a repeating dichotomy between the Protagonist and

the Sole Companion. Typically, one of the pair is relatively unstable

(Reese, Marie, Barry), while the other is more psychologically

grounded. One is a far more capable (Reese, Bourne, Lena), while the

other, not so much. Which member of the pair has which trait depends on the story's premise, yet there is clear evidence that

these “odd couple” pairings are fairly common to this subtype.

The relationship need not necessarily be romantic either. It may be

“bro-mantic,” (like that between the two leads in Pineapple

Express), a paternal or maternal

bond, (like that which forms between John Connor and his cyborg

protector in Terminator 2),

or one based on trust and mutual

respect, (such as the friendship between Andy and Red in The

Shawshank Redemption.)

PLOT BREAKDOWN

ACT 1

Setup

Sequence

Structurally,

a Destructive Beast's setup sequence does not differ much from the

norm. The Protagonist may already be targeted by the Beast, giving

the setup an air of menace, or the targeting may not have yet

occurred. If the Protagonist has already been targeted, neither the

Protagonist nor the audience will know this. Instead, the Beast's

intentions are kept a mystery. In some cases, the Beast may not need

to appear in the setup at all. Likewise, the setup may or may not

introduce the Sole Companion character. If the character does appear,

no meaningful relationship yet exists between Sole Companion

and Protagonist.

Inciting

Incident

The

inciting incident occurs with an action through which the

audience becomes aware that the

Protagonist has been targeted by the Beast. With this event, the

Beast takes its first decisive action to ensnare the Protagonist. The

cyborg starts killing women named Sarah Connor. Conklin starts

tracking Bourne. The phone sex operator tries to coerce Barry into

giving her money. However, at this early point, the Protagonist

either remains largely unaware of the threat or does not yet realize

how serious this threat may be. Sarah Connor hears of the murders,

but could not yet possibly understand the full scope of the

situation. Jason Bourne suspects he may be in danger, but has no idea

why. Barry becomes agitated, but thinks can solve the problem by

simply canceling his credit card. The full threat does not become

apparent to the Protagonist - or the audience - until the End of

First Act Turning Point.

The End of

First Act Turning Point

Two important

events occur at the end of the first act, separately but typically in

succession (the order is unimportant). First, the Beast officially

begins the hunt by launching its first major “attack” on the

Protagonist. The cyborg makes its first attempt to kill Sarah Connor

at a nightclub. Conklin activates three assassins to put “Bourne

in a body bag.” Barry's Beast sends goons to beat and rob him.

The end of

the first act must also feature a moment where the relationship

between Protagonist and Sole Companion officially begins. This could

be something decisive (Reese's “Come with me if you want to live”),

something more unassuming (Bourne recruits Marie to drive him to

Paris), or the start of a personal relationship (Lena asks Barry out

to dinner and Barry accepts). Regardless of how it occurs, the

important thing is that these two characters have transitioned from

separate individuals into a pair.

ACT 2A

Part 1

The

Beast is still chasing the Protagonist, whether this be physically

occurring on screen like in Terminator,

or largely unseen in the background like in Bourne and

Punch-Drunk. However,

at this moment, this action is of secondary importance. More

importantly, the first sequence(s) of Act 2A is where the Protagonist

and Sole Companion must grow comfortable with each other and

reconcile the nature of their relationship. One or both characters

will have doubts or fears over whether this relationship should be

continued. Sarah fears that Reese is insane. Jason Bourne seems to be

more trouble than Marie wants to handle. Barry is scared of women.

However this dilemma must be solved quickly when the Beast attacks

again, creating the turning point that ends the sequence.

Part 2

The

Beast makes its second major attack. The cyborg invades the police

station. The first assassin attacks Bourne in his home. The goons

beat up and rob Barry. This stretch of the narrative becomes all

about escape. It may last for one sequence or two, but by the time

Act 2A ends, the Protagonist is forced to come to two strong

conclusions. First, the Protagonist becomes convinced that he/she and

the Sole Companion must stick together. This solidifies the

relationship between the two characters. (I find it inconsequential

that Lena is unaware of Barry's struggle with the Beast in

Punch-Drunk Love. She

fulfills the same function as Reese or Marie regardless. It is

impossible to think that Barry could overcome his fight with the

Beast had he not chosen to continue to receive Lena's love and

support.) Second, the Protagonist realizes that the Beast will never

stop attacking him or her. It will keep coming and coming.

Because of this, the Protagonist can see only one reasonable option

at the moment: tactical retreat.

ACT 2B

Part 1

The

Protagonist escapes to a safe location with the Sole Companion. Sarah

and Reese find haven, first under a highway overpass and then in a

cheap motel. Bourne and Marie also hole up in a hotel. Barry runs

further than everyone, fleeing all the way to Hawaii to find some

peace with Lena. Here, the Protagonist can regroup and come up with

some sort of plan. The Protagonist is able to do so only because

Beast has also found itself in a situation where it must regroup. The

Beast has momentarily lost the trail of its target and must take

action to once again pick up the scent.

Like Part 1

of Act 2A, this sequence is far more about the relationship between

Protagonist and Sole Companion than the Protagonist and the Beast. In

this brief respite, the pair transform into a domestic couple,

“playing house” even. In all three study films, this is the point when

Protagonist and Sole Companion consummate their romantic

relationship. Yet this sweet stability is broken by the next turning

point. The Beast learns of their location. It is coming for them yet

again.

Part 2

Though

some time may remain for the Protagonist to take actions and

implement his or her new plan before the Beast arrives, eventually

the Beast will come and launch a stronger and far more brutal assault

than ever before. The Terminator,

being the shortest and simplest of our study films, takes an

uncomplicated route by using this attack to transition into the long

battle that comprises Act 3. Bourne

and Punch-Drunk take

somewhat longer routes that mirror each other plot point for plot

point. Both Protagonists are attacked by the Beast's proxy. The

Protagonist defeats these proxies, but rather than be pleased with

the victory, the Protagonist is FURIOUS. This time, the Beast has not

only tried to harm him, but the innocent people he cares about. Both

Bourne and Barry are fed up. They want to end this. And they realize

only way to do so is to square off with the Beast face-to-face. In

both Bourne and

Punch-Drunk, the

Protagonist speaks directly to the Beast for the first time and

challenges it to a fight. This challenge sets up the battle that will

make up Act 3.

ACT 3

In

general, Act 3 develops as would be expected in a restorative

three-act narrative. There is an conflict-intensifying sequence that

leads to the final confrontation between Protagonist and Beast, a

turning point, and then the final confrontation itself. (I should

point out that the final action sequence found in The

Bourne Identity is much

different than the one originally written. The filmmakers decided to

change the ending in response to the events of 9/11. It was supposed

to be a more intense, explosion-filled ending, much like that seen in

The Terminator, as

opposed to the more subdued end seen in the final film.)

There

is one significant point that must be made about these final

sequences. Whether it happens midway through the act or very late, at

some point the relationship between predator and prey will reverse.

The Protagonist does this by entrapping

the Beast. Whether it be Sarah Connor encaging the cyborg inside the

mechanical press, Jason Bourne cornering Conklin in the safehouse, or

Barry staring down his tormentor in the back of the mattress store,

this act robs the Beast of its power and ability to intimidate. The

big, bad Beast has suddenly turned pathetic and weak. With this

reversal of power, the Protagonist can finally defeat the Beast,

either by destroying it or forcing it to back down.

…........

Despite

appearances, the Destructive Beast plot subtype is about far more

than predator and prey. Any good story is “about more than it is

about.” A story that lacks any meaning beyond the observable

actions of its plot is always a mediocre one. Hence, I have found two

surprising traits shared by every one of these stories.

THESE ARE STORIES ABOUT HUMANE RELATIONSHIPS

The battle

with the Beast may provide the action and conflict. It may provide

the excitement and commercial appeal. But the real meaning in these

films emerges from the warm, humane, multifaceted relationship

between Protagonist and Sole Companion set in contrast with the cold,

inhumane relationship between Protagonist and Beast.

Left to his

or her own devices, the Protagonist would in all inevitability

succumb to the force of the Beast. However, through the

relationship between Protagonist and Sole Companion, the

Protagonist's character gains something it did not have previously, which allows

him/her to defeat the Beast. To understand how and why, we must

ask two questions: “For what reason does the Beast target the

Protagonist?” and “For what reason does the Sole Companion remain

attached to the Protagonist despite reasons not to?”

As

I have mentioned, the Beast is a single-minded creature. It targets

the Protagonist for a singular quality which it believes warrants the

Protagonist's destruction. The machines of the future target Sarah

Connor because they see her as a weakling that can be easily

wiped out. The CIA's Treadstone sees Jason Bourne as nothing more

than a soulless killing machine that needs to be deactivated. Barry's

extortionists see him as a pathetic wimp with whom they

can do whatever they please. More importantly, the Protagonist begins

the story seeing him or herself

in the same way. Sarah believe she is a weak nothing. Bourne feels

that he has lost all humanity. Barry sees himself as a pathetic wimp.

It seems the Protagonists agrees with the Beast. If this is the

case, the Protagonist might eventually give in and let the Beast win.

But if these

Protagonists really are such undesirable monotypes, why do their Sole

Companions risk so much to stick by their sides? The Sole Companion

remains loyal to the Protagonist because he or she is the only person

in the whole wide world who sees MORE in the Protagonist. Through

their personal relationship, the Sole Companion realizes that the

Protagonist is far more than the trait for which he or she has been

targeted. Instead, the Sole Companion recognizes so many other

qualities that make the Protagonist a worthwhile human being. Reese sees

strength and courage in Sarah Connor that Sarah herself does not

admit. Marie knows that Jason Bourne is not just a killing machine,

but a good man with a good heart. Lena sees charm and beauty in Barry

where everyone else can only see the wimp. Through this relationship,

the Protagonist's sense of self transforms from the negative

monotypical view shared by the Beast, to the positive multifaceted

one of the Sole Companion. Strengthened by the Sole Companion's

support, the Protagonist is able to stand up and say, “I am a

worthwhile individual. I do not deserve this treatment. I am greater

than the Beast and can defeat it.”

Why is this

transformation so important? Aside from the pragmatic narrative

concerns of story structure and character arc, this relationship

provides the context through which the audience receives the story's

true meaning. By recognizing the value of an individual in the face

of overwhelming persecution, we learn this story subtype's subtextual

theme.

THESE STORIES ARE THEMATIC CONDEMNATIONS OF PERSECUTION

In every

historical case of persecution, whether it be against an entire race

or a single individual, the persecutor dehumanizes its victim by

degrading the whole of that person's identity to a single

undesirable trait. The persecutor does not see a unique individual

with many different qualities, but only a race, a religion, a

political view, or some type of behavior with negative associations. By defining its victim with one undesirable trait, the

victim is turned into something no better than an animal. A dog is

just a dog. A roach is like any other roach. A rat can be nothing

more than a rat. And like any bothersome animal, the persecutor feels

justified in exterminating the person for what it sees as the greater

good.

This is why

social persecution is morally wrong. It is based on a lie. No

person's existence is defined by a single trait by which he or she

should be accepted or condemned. We are all unique individuals,

possessing hundreds of personal qualities, each with its own

potential to add worth and value to the world. As unique individuals,

each one of us has the right to prove our value on our own terms –

not by one or two isolated behaviors, but through all of them as a

whole. If an individual's worth is to be judged, it should not be donw by

some mechanical-minded aggressor with no regard for the individual's

humanity, but by the people who know and understand them.

Stories of

the Destructive Beast subtype exist as lessons on social persecution.

They show us the value of an individual's humanity by pitting it

against an unthinking, uncaring force that chooses to ignore its

victim's basic right to exist – the right to live, to love, and to

bring value to their world in their own way. The Beast then not

only represents evil as it exists in the narrative, but the social

evils that continue to persecute innocent victims in our own world.