|

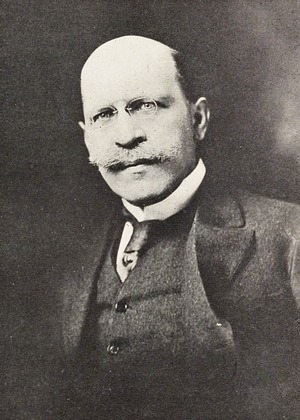

Hugo Münsterberg: Maverick psychologist

and lord of the umlaut.

|

Ninety-seven years

ago, German-American psychologist Hugo Münsterberg

published what would be one of the first analytical studies of

the emerging art of cinema, “The Film: A Psychological Study.”

Though movies in Münsterberg’s

time (1916) were still quite primitive, Münsterberg

arrives at a very bold conclusion while comparing drama written for

the stage to that intended for the screen: The further away an art

form’s methods of expression are from the realities of the physical

world (time, space, and concrete physicality), the more potential it

has to impact the viewer’s mental

world, (the realms of thought, memory, and emotion). Movies construct completely artificial worlds that present drama through a discourse

inconsistent with the rules of physical existence. Cinema tells its

stories through peculiar qualities not found in the theatre – or

any of the other arts for that matter. Though these qualities run

counter to the experiences of life as we know it, they work to give

the audience the illusion of a heightened un-reality which requires

and elicits much greater mental and emotional involvement. A wise

screenwriter will not only be aware of these peculiar qualities, but

makes use of them to absorb the audience into their fictional worlds

and create the most emotionally stimulating experience.

Belief

& Plausibility

For

a large part, films create their heightened state of un-reality

automatically by way of the physical properties of cinema. In

theater, a paradox exists where the physical presence of dramatic

actions and performers makes the drama feel less

real to an audience. In theater, the backdrop and performers stand in

the same plane of existence as the audience. The audience could reach

out and touch them if they wish. However, this causes the audience to

remain fully aware of the story’s artificiality. They know the

stage is not really 19th

century London, only a depiction of it. They know the persons on the

stage are not really Sherlock Holmes or Jack the Ripper, but only

performers making pretend. To become mentally involved in the drama, and

audience must “suspend their disbelief” in the drama’s

artificiality. The physical presence of the stage prevents the

theatrical audience from ever accomplishing this in full. They can only

choose to play along with the story, but never fully surrender to its

reality.

This

is not so with cinema. Though a film presents its drama through far

more artificial means than the theatre (an incongruent series of

highly-manipulated two-dimensional images rather than the presence of

flesh-and-blood human beings) cinema has the ability to immerse its

audience in a world that not only looks like 19th

century London, but leads the audience to temporarily accept the

illusion that it is indeed

19th

century London, even though the audience knows it is impossible to

travel to such a time. Such immersion encourages the audience to no

longer see the actors as mere imitators of Holmes or the Ripper, but

as the real McCoy themselves. Thus, when well-handled, the physical

properties of cinematic discourse cause the audience to fully suspend

their disbelief and accept the illusion.

Once

this illusion has been formed, the storyteller’s job is to simply

avoid screwing things up by breaking the illusion. Anything that

should sabotage the fantasy by pointing out its artificiality will

pull the audience out of the un-reality and cause them to cease their

mental participation. I do not mean that a cinematic story cannot

contain things the audience knows cannot exist in reality, such as

the fantastic, the supernatural, or the unreal. In fact, such things

are what the cinema is more successful than any other art at

portraying. What I mean is that a cinematic story’s characters and

events must maintain the illusion of reality by following an

internal logic that parallels the logic found in the real world. A

film’s artificial world continues to feel real when its events follow

the same logic by which events occur in real life. The cinematic

story is not enslaved to the possible,

but to what is plausibile.

Aristotle

wrote “Plausible impossibilities are preferable to implausible

possibilities.” This means anything can happen in a story as long

as events make reasonable sense based upon what has occurred before

them. Any way the story world is different from the real world must be

established at the story’s beginning. Anything not established as

different will be expected to behave by the normal rules of reality. The established concepts then become the

story’s “rules.” If a story should break its own established rules,

if an event should occur without reasonable explanation, if a person

should suddenly behave out of character or act without

understandable motivation, the viewer becomes suddenly aware that he

or she is watching a poorly-constructed lie. Like a dreamer becoming

conscious of the fact that he or she is asleep, viewers will snap out

of the illusion, re-engage their disbelief, and refuse continued

participation.

Point

of View

In the theatre, the audience's point of view never changes. No matter

what occurs on stage, the viewer can only observe the action from the angle of his or her particular seat in the audience. The space separating seat from stage distances the viewer emotionally from the story’s action.

Events can only be perceived through the eyes of an uninvolved

observer, like a voyeur spying into the story’s world through a

keyhole.

Cinema, on the other hand, has the ability to put the audience right

in the middle of the action. The viewer is allowed to experience

story action as a controlled stream of consciousness, created by the

constant refocusing of the viewer’s perspective (through camera and editing) to deliberately-chosen points of view. Point of view does not only have the effect of

immersing the audience into the story’s reality, but also shapes

and informs the perception of that reality. Its skilled use not

only allows the audience to become mentally involved in the story’s

events, but feel an emotional bond to the story’s characters, since

point of view also allows the audience to see events in ways which are as close as

possible to the characters’ own perspective. The audience sees this world

as the character sees it, forging a connection between the two in a manner

impossible to achieve in the theatre.

Though a scene’s visual points of view are ultimately chosen by the

director and editor, screenwriters should not write scenes as if they

were sitting in a theatre audience casually transcribing the events

on stage. Point of view is the writer’s responsibility as well.

Have some conception as to the scene’s point of view before writing

begins. A writer should communicate the action of a scene in a way

that leads the reader’s imagination the same way camera and editing

lead the eye. Good writing does not explicitly express how a scene

should be shot, but will to imply shots through well-chosen language

to indicate where the dramatic focus should lie. All of a scene’s

contents are not equal. What in the scene demands the audience's

attention? What is important to communicate? The character’s

reactions and emotions? The physical action being performed? A dirty

spot on the wall? Construct the scene to connote when and how actions

will be perceived.

Time

& Space

In theatre, the action of a scene is beholden to the natural rules of

time and space. The location cannot abruptly change, and time must

move forward at its standard pace. Cinema, on the other hand, has no

such limitations. It can go from place to place as it pleases. Time

can leap forward or backward at will. Time can also freeze, slow

down, or move in reverse. A savvy screenwriter knows how to use the

freedom of time and space to deliver drama in its most effective and

mentally stimulating form.

Hitchcock famously said, “Drama is life with the dull bits cut

out.” So cut them out! Give the audience only the most essential,

most dramatic, most emotionally-evocative slices of time with none of

the dead space in between. In this regard, the work of the

screenwriter is much like that of the film editor. In real life, time

unspools in one long seamless thread, capturing every moment,

meaningful or insignificant, like frames preserved onto an endless

reel of celluloid. In life as in art, few things have meaning in

isolation. The meaning of events can often only be acquired in

relation to other events. Unfortunately, it is difficult to identify

the true significance of an individual real-life event as it occurs

since its causal relationships to other events is diluted or

completely washed away by the tedious slow-drip of time and the clutter of minutia separating them. The realities of linear

time thus cause events in life to often seem isolated rather than

connected to a whole.

The cinematic storyteller has been given the power to overcome this.

The storyteller takes the hypothetical spool of time which exists in a

fictional story world and surgically removes all portions except

those which serve authorial intentions. All excess is removed until

only moments of significance remain. The storyteller then transposes the

order of events so that they occur in an explicitly chosen succession (this remains true whether the storyteller chooses to obey temporal linearity or

not). Due to this manipulation, the audience is able to see clear

connections between the story’s events, and thus a sense of

constantly-developing meaning between them.

This

time-editing refers not only to the storyteller’s removal of

unimportant events between scenes, but the whittling away of all

unnecessary moments within the scenes themselves. The old saw is that

scenes should “start late, end early.” Taking this advice ensures

that each scene contains only meaningful moments that move the story

forward without unnecessary filler slowing things down.

Cinematic worlds are time-accelerated worlds that contain only

moments which have dramatic significance. This time-acceleration

keeps the viewer mentally involved. He or she must pay attention or

be left behind. At the same time, the viewer becomes creatively

involved as he or she is expected to use cognitive imagination to

fill in the gaps and form mental connections between events.

Accelerated time creates heightened awareness, which leads to greater

mental and emotional involvement on the part of the viewer.

Structure

As

the cinematic form flouts reality’s physical rules, it must invent

its own rules to keep its internal microcosm from collapsing. The

theatre remains somewhat stable in its discourse by being grounded in

the here and now. The cinema, on the other hand, with the unreality of

its discourse, has no choice but to replace the rules of reality with

the rules of narrative. With narrative structure, the viewer receives

a stable, yet still plausible, illusion of reality that will actually

function at a higher level than the world in which we live.

As

stated in my book Screenwriting

Down to the Atoms,

stories are not reflections of reality. They are analogues

of

reality. Stories are pleasurable because they present worlds which function in ways we wish our world would operate. One

reason life can be so frustrating is that real life lacks structure.

Events in life seem to occur randomly. Problems invade without

provocation. Actions taken often fail to produce results. Things seem

to move in multiple directions at once – or not move at all –

leaving us anxious and confused over whether life has any purpose or

goal. Stories, in contrast, present worlds where everything happens

for a reason. Every event is connected and designed to lead to a

logical end. Stories comfort audiences with worlds where everything

has order and meaning.

This

cannot be accomplished without narrative structure. On this subject,

Münsterberg

likens the work of a screenwriter to that of a composer. No matter

how bold or innovative a composer may be, each melody must still obey

some sort of internal structure to unify the piece, or else the music

becomes chaotic and aesthetically displeasing. Like the

structure of music, narrative structure provides a rhythm and flow

that gives a sensation of order and control to its events.

As

Münsterberg

also points out, cinematic structure begins with a simple of

unity of action.

Like a musical work, a cinematic narrative is isolated and

self-contained. It has a beginning and an end. Everything in between

must follow a single linear thread that grows and develops as time

progresses, orientated around the singular premise established at the

story’s beginning. Unlike how events occur in real life, the course of

a narrative should be free of any distracting elements which do not

relate to the premise. Unrelated material will damage a story’s

unity the way the inclusion of random errant notes would weaken a

musical piece. By focusing the narrative upon one tightly-structured

line of action, the storyteller leads the audience to find meaning

and emotional fulfillment in events that would be impossible in the

distracting chaos of real life.

Conclusion

If anything should be taken away from all of this, it is that a good

cinematic story does not provide the audience with reality. Rather,

it uses its abilities to defy reality to create a heightened illusion

of existence with the capacity to trigger viewer thoughts,

emotions, and imaginations, absorbing the viewer in a world where they are

mental participants rather than uninvolved observers. This is the

magic of cinema. This is what allows its stories more emotional

impact than any other dramatic form. This is what the cinematic storyteller

must use his or her skills to do.

No comments:

Post a Comment